Making Choices

Our previous lessons have shown us how to manipulate data, define our own functions, and repeat things. However, the programs we have written so far always do the same things, regardless of what data they're given. We want programs to make choices based on the values they are manipulating. To help us see what decisions they're making, we'll start by looking at how computers manipulate images.

Objectives

- Create a simple "image" made out of colored blocks.

- Explain how the RGB model represents colors.

- Explain the similarities and differences between tuples and lists.

- Write conditional statements including

if,elif, andelsebranches. - Correctly evaluate expressions containing

andandor. - Correctly write and interpret code containing nested loops and conditionals.

- Explain the advantages of putting frequently-modified code in a function.

Image Grids

Let's start by creating some simple heat maps of our own using a library called ipythonblocks. The first step is to create our own "image":

from ipythonblocks import ImageGrid

Unlike the import statements we have seen earlier, this one doesn't load the entire ipythonblocks library. Instead, it just loads ImageGrid from that library, since that's the only thing we need (for now).

Once we have ImageGrid loaded, we can use it to create a very simple grid of colored cells:

grid = ImageGrid(5, 3) grid.show()

Just like a NumPy array, an ImageGrid has some properties that hold information about it:

print 'grid width:', grid.width print 'grid height:', grid.height print 'grid lines on:', grid.lines_on

grid width: 5 grid height: 3 grid lines on: True

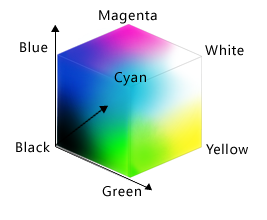

The obvious thing to do with a grid like this is color in its cells, but in order to do that, we need to know how computers represent color. The most common schemes are RGB, which is short for "red, green, blue". RGB is an additive color model: every shade is some combination of red, green, and blue intensities. We can think of these three values as being the axes in a cube:

An RGB color is an example of a multi-part value: like a Cartesian coordinate, it is one thing with several parts. We can represent such a value in Python using a tuple, which we write using parentheses instead of the square brackets used for a list:

position = (12.3, 45.6) print 'position is:', position color = (10, 20, 30) print 'color is:', color

position is: (12.3, 45.6) color is: (10, 20, 30)

We can select elements from tuples using indexing, just as we do with lists and arrays:

print 'first element of color is:', color[0]

first element of color is: 10

Unlike lists and arrays, though, tuples cannot be changed after they are created—in technical terms, they are immutable:

color[0] = 40 print 'first element of color after change:', color[0]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-11-9c3dd30a4e52> in <module>()

----> 1 color[0] = 40

2 print 'first element of color after change:', color[0]

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

If a tuple represents an RGB color, its red, green, and blue components can take on values between 0 and 255. The upper bound may seem odd, but it's the largest number that can be represented in an 8-bit byte (i.e., 28-1). This makes it easy for computers to manipulate colors, while providing fine enough gradations to fool most human eyes, most of the time.

Let's see what a few RGB colors actually look like:

row = ImageGrid(8, 1) row[0, 0] = (0, 0, 0) # no color => black row[1, 0] = (255, 255, 255) # all colors => white row[2, 0] = (255, 0, 0) # all red row[3, 0] = (0, 255, 0) # all green row[4, 0] = (0, 0, 255) # all blue row[5, 0] = (255, 255, 0) # red and green row[6, 0] = (255, 0, 255) # red and blue row[7, 0] = (0, 255, 255) # green and blue row.show()

Simple color values like (0,255,0) are easy enough to decipher with a bit of practice, but what color is (214,90,127)? To help us, ipythonblocks provides a function called show_color:

from ipythonblocks import show_color show_color(214, 90, 127)

It also provides a table of standard colors:

from ipythonblocks import colors c = ImageGrid(3, 2) c[0, 0] = colors['Fuchsia'] c[0, 1] = colors['Salmon'] c[1, 0] = colors['Orchid'] c[1, 1] = colors['Lavender'] c[2, 0] = colors['LimeGreen'] c[2, 1] = colors['HotPink'] c.show()

Challenges

Fill in the

____in the code below to create a bar that changes color from dark blue to black.bar = ImageGrid(10, 1) for x in range(10): bar[x, 0] = (0, 0, ____) bar.show()Why do computers use red, green, and blue as their primary colors?

Conditionals

The other thing we need in order to create a heat map of our own is a way to pick a color based on a data value. The tool Python gives us for doing this is called a conditional statement, and looks like this:

num = 37

if num > 100:

print 'greater'

else:

print 'not greater'

print 'done'

not greater done

The second line of this code uses the keyword if to tell Python that we want to make a choice. If the test that follows it is true, the body of the if (i.e., the lines indented underneath it) are executed. If the test is false, the body of the else is executed instead. Only one or the other is ever executed:

Conditional statements don't have to include an else. If there isn't one, Python simply does nothing if the test is false:

num = 53

print 'before conditional...'

if num > 100:

print '53 is greater than 100'

print '...after conditional'

before conditional... ...after conditional

We can also chain several tests together using elif, which is short for "else if". This makes it simple to write a function that returns the sign of a number:

def sign(num):

if num > 0:

return 1

elif num == 0:

return 0

else:

return -1

print 'sign of -3:', sign(-3)

sign of -3: -1

One important thing to notice the code above is that we use a double equals sign == to test for equality rather than a single equals sign because the latter is used to mean assignment. This convention was inherited from C, and while many other programming languages work the same way, it does take a bit of getting used to...

We can also combine tests using and and or. and is only true if both parts are true:

if (1 > 0) and (-1 > 0):

print 'both parts are true'

else:

print 'one part is not true'

one part is not true

while or is true if either part is true:

if (1 < 0) or ('left' < 'right'):

print 'at least one test is true'

at least one test is true

In this case, "either" means "either or both", not "either one or the other but not both".

Challenges

TrueandFalsearen't the only values in Python that are true and false. In fact, any value can be used in aniforelif. After reading and running the code below, explain what the rule is for which values are considered true and which are considered false. (Note that if the body of a conditional is a single statement, we can write it on the same line as theif.)if '': print 'empty string is true' if 'word': print 'word is true' if []: print 'empty list is true' if [1, 2, 3]: print 'non-empty list is true' if 0: print 'zero is true' if 1: print 'one is true'Write a function called

nearthat returnsTrueif its first parameter is within 10% of its second andFalseotherwise. Compare your implementation with your partner's: do you return the same answer for all possible pairs of numbers?

Nesting

Another thing to realize is that if statements can be combined with loops just as easily as they can be combined with functions. For example, if we want to sum the positive numbers in a list, we can write this:

numbers = [-5, 3, 2, -1, 9, 6]

total = 0

for n in numbers:

if n >= 0:

total = total + n

print 'sum of positive values:', total

sum of positive values: 20

We could equally well calculate the positive and negative sums in a single loop:

pos_total = 0

neg_total = 0

for n in numbers:

if n >= 0:

pos_total = pos_total + n

else:

neg_total = neg_total + n

print 'negative and positive sums are:', neg_total, pos_total

negative and positive sums are: -6 20

We can even put one loop inside another:

for consonant in 'bcd':

for vowel in 'ae':

print consonant + vowel

ba be ca ce da de

As the diagram below shows, the inner loop runs from start to finish each time the outer loop runs once:

We can combine nesting and conditionals to create patterns in an image:

square = ImageGrid(5, 5)

for x in range(square.width):

for y in range(square.height):

if x < y:

square[x, y] = colors['Fuchsia']

elif x == y:

square[x, y] = colors['Olive']

else:

square[x, y] = colors['SlateGray']

square.show()

This is our first hand-made data visualization: the colors show where x is less than, equal to, or greater than y.

Challenges

Will changing the nesting of the loops in the code above—i.e., wrapping the Y-axis loop around the X-axis loop—change the final image? Why or why not?

Python (and most other languages in the C family) provides in-place operators that work like this:

x = 1 # original value x += 1 # add one to x, assigning result back to x x *= 3 # multiply x by 3 print x 6Rewrite the code that sums the positive and negative numbers in a list using in-place operators. Do you think the result is more or less readable than the original?

Creating a Heat Map

The last step is to turn our data into something we can see. As in previous lessons, the first step is to get the data into memory:

import numpy as np data = np.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',') print 'data shape:', data.shape

data shape: (60, 40)

The second is to create an image grid that is the same size as the data:

width, height = data.shape heatmap = ImageGrid(width, height)

(The first line of the code above takes advantage of a neat trick: we can unpack the values in a tuple by assigning it to as many variables as it has entries.)

The third step is to decide how we are going to color the cells in the heat map. To keep things simple, we will use red, green, and blue as our colors, and compare data values to the data set's mean. Here's the code:

for x in range(width):

for y in range(height):

if data[x, y] < data.mean():

heatmap[x, y] = colors['Red']

elif data[x, y] == data.mean():

heatmap[x, y] = colors['Green']

else:

heatmap[x, y] = colors['Blue']

heatmap.show()

This may be what we asked for, but both the image and the code are hideous:

- It's too large for us to view the whole thing at once on a small laptop screen.

- Our first heatmap had time along the X axis; this seems to have time along the Y axis.

- Red against blue is pretty hard on the eyes.

- The heatmap only shows two colors because none of the (integer) measurements has exactly the same value as the (fractional) mean.

- We are calculating the mean of

dataeither once or twice each time we go through the loop. That means that on a 40×60 data set, we are performing the same calculation 2400 times.

Here's how we can improve it:

- We can give

ImageGridan optional parameterblock_sizeto set the size of each block. - We can transpose our data before creating the grid.

- We can pick better colors (I'm personally fond of orchid, fuchsia, and hot pink).

- Instead of checking if values are exactly equal to the mean, we can see if they are close to it.

- We can calculate the mean once, before we start our loops, and use that value over and over.

Our modified code looks like this:

flipped = data.transpose()

width, height = flipped.shape

heatmap = ImageGrid(width, height, block_size=5)

center = flipped.mean()

for x in range(width):

for y in range(height):

if flipped[x, y] < (0.8 * center):

heatmap[x, y] = colors['Orchid']

elif flipped[x, y] > (1.2 * center):

heatmap[x, y] = colors['HotPink']

else:

heatmap[x, y] = colors['Fuchsia']

heatmap.show()

That's a bit better—but now the contrast between the colors isn't great enough. And there still aren't very many fuchsia cells: we may want to widen the band around the mean that gets that color.

We could rewrite our loop a third time, but the right thing to do is to put our code in a function so that we can experiment with bands and colors more easily.

def make_heatmap(values, low_color, mid_color, high_color, low_band, high_band, block_size):

'''Make a 3-colored heatmap from a 2D array of data.'''

width, height = values.shape

result = ImageGrid(width, height, block_size=block_size)

center = values.mean()

for x in range(width):

for y in range(height):

if values[x, y] < low_band * center:

result[x, y] = low_color

elif values[x, y] > high_band * center:

result[x, y] = high_color

else:

result[x, y] = mid_color

return result

To test this function, we'll run it with the settings we just used:

h = make_heatmap(flipped, colors['Orchid'], colors['Fuchsia'], colors['HotPink'], 0.8, 1.2, 5) h.show()

That seems right, so let's widen the band and use more dramatic colors:

h = make_heatmap(flipped, colors['Gray'], colors['YellowGreen'], colors['SpringGreen'], 0.5, 1.5, 5) h.show()

We'll probably want to experiment a bit more before publishing, but writing a function has made experimenting easy. We can make it even easier by re-defining our function one more time to give the parameters default values. While we're at it, let's put the low and high bands at the front, since they're more likely to change than our color choices:

def make_heatmap(values,

low_band=0.5, high_band=1.5,

low_color=colors['Gray'], mid_color=colors['YellowGreen'], high_color=colors['SpringGreen'],

block_size=5):

'''Make a 3-colored heatmap from a 2D array of data.

Default color scheme is gray to green.'''

width, height = values.shape

result = ImageGrid(width, height, block_size=block_size)

center = values.mean()

for x in range(width):

for y in range(height):

if values[x, y] < low_band * center:

result[x, y] = low_color

elif values[x, y] > high_band * center:

result[x, y] = high_color

else:

result[x, y] = mid_color

return result

Once default values are added, the function's first line is too long to fit comfortably on our screen. Rather than breaking it wherever it hits the right edge of the screen, we have divided the parameters into logical groups to make it more readable.

Again, our first test is to re-run it with the same values as before (which we give it in a different order, since we've changed the order of parameters):

h = make_heatmap(flipped, 0.5, 1.5, colors['Gray'], colors['YellowGreen'], colors['SpringGreen'], 5) h.show()

We can now leave out everything except the data being visualized, or provide the data and the bands and re-use the default colors and block size:

h = make_heatmap(flipped, 0.4, 1.6) h.show()

We can now explore our data with just a few keystrokes, which means we can concentrate on our science and not on our programming.

Challenges

Why did we transpose our data outside our heat map function? Why not have the function perform the transpose?

Why does the heat map function return the grid rather than displaying it immediately? Do you think this is a good or bad design choice?

Explain what the overall effect of this code is:

temp = left left = right right = tempCompare it to:

left, right = right, leftDo they always do the same thing? Which do you find easier to read?

Key Points

- Use the

ImageGridclass from theipythonblockslibrary to create simple "images" made of colored blocks. - Specify colors use (red, green, blue) triples, each component of which is an integer in the range 0..255.

- Use

if conditionto start a conditional statement,elif conditionto provide additional tests, andelseto provide a default. - The bodies of the branches of conditional statements must be indented.

- Use

==to test for equality. X and Yis only true if both X and Y are true.X or Yis true if either X or Y, or both, are true.- Zero, the empty string, and the empty list are considered false; all other numbers, strings, and lists are considered true.

- Nest loops to operate on multi-dimensional data.

- Put code whose parameters change frequently in a function, then call it with different parameter values to customize its behavior.

Next Steps

Our final heatmap function is 17 lines long, which means that if there's a 95% chance of each line being correct, the odds of the whole function being right are only 41%. Before we go any further, we need to learn how to test whether our code is doing what we want it to do, and that will be the subject of the next lesson.