Large Scale Computation with HTCondor

Overview

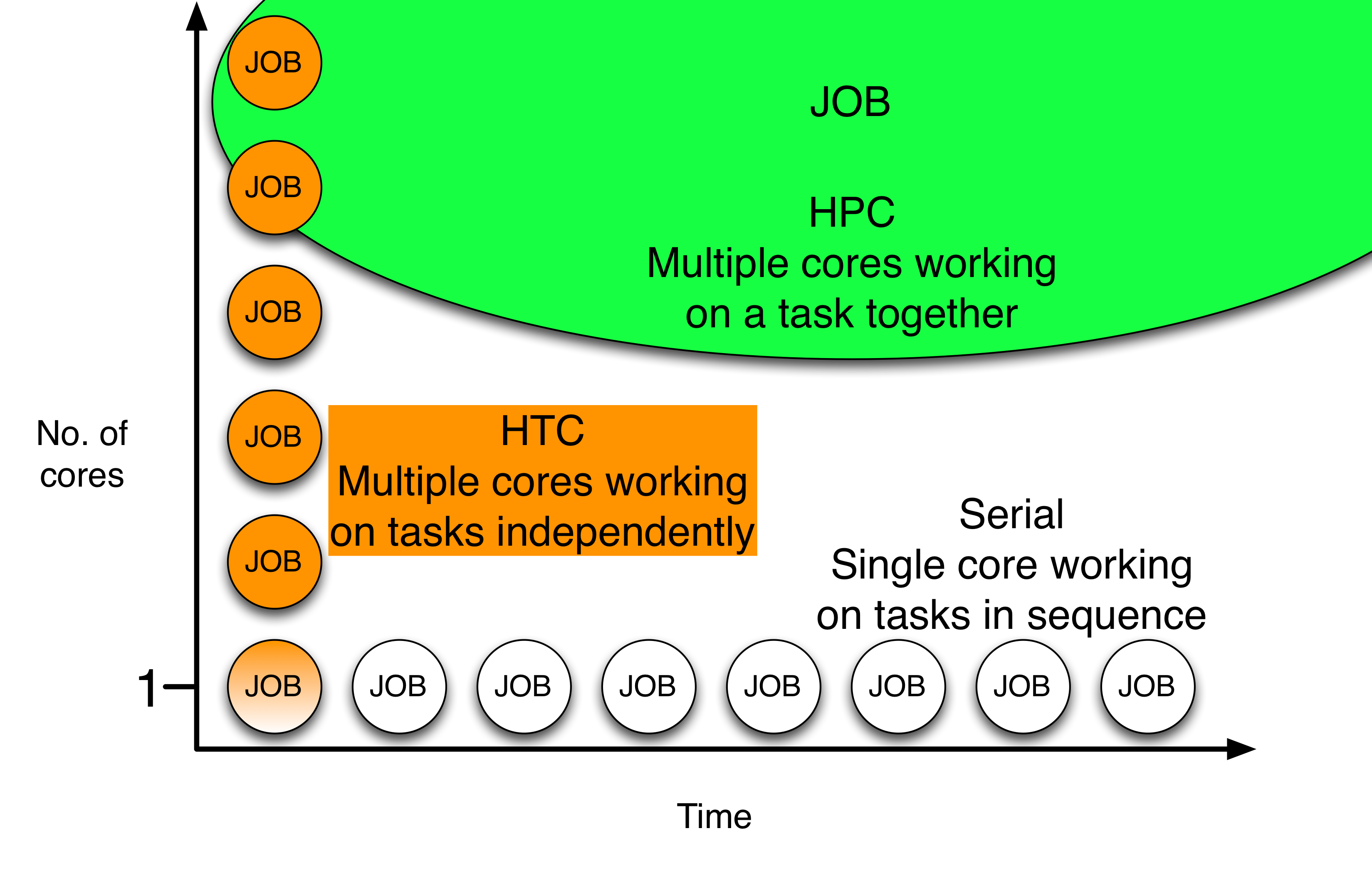

To harness to full abilities of distributed high throughput computing on the OSG, HTCondor allows the user to easily submit and manage large numbers of jobs. While serial computing executes one task at a time (on one or even few CPUs) and HPC execution modes rely on specialized software to coordinate multiple CPU cores (typically accompanied by queue waiting times to achieve the total number of requisit cores), an HTC approach requires the execution of many independent jobs, each on one core (or few cores), but without the need for synchronization.

Though the previous exercises used queue 1 to submit a single job with each submit file,

the queue line of an HTCondor submit file can be used in various ways to indicate

that multiple jobs should be submitted according to the submit file contents, and can be

used in combination with other submit file contents to indicate what's different about

eah job. (This is one of the most iimportant reasons for having separate submit and executable

files.)

Once we understand the basic HTCondor script to run a single job, it is easy to scale up.

Move out of the tutorial-quickstart directory (back to your home directory) and grab a

new tutorial that will demonstrate examples for submitting multiple jobs at once:

$ cd

$ tutorial ScalingUp-Python

$ cd tutorial-ScalingUp-Python

The tutorial-ScalingUpdd-Python directory contains sets of files for the below examples,

including a sample Python program, job description files, and executable files.

A Job with a Python Script

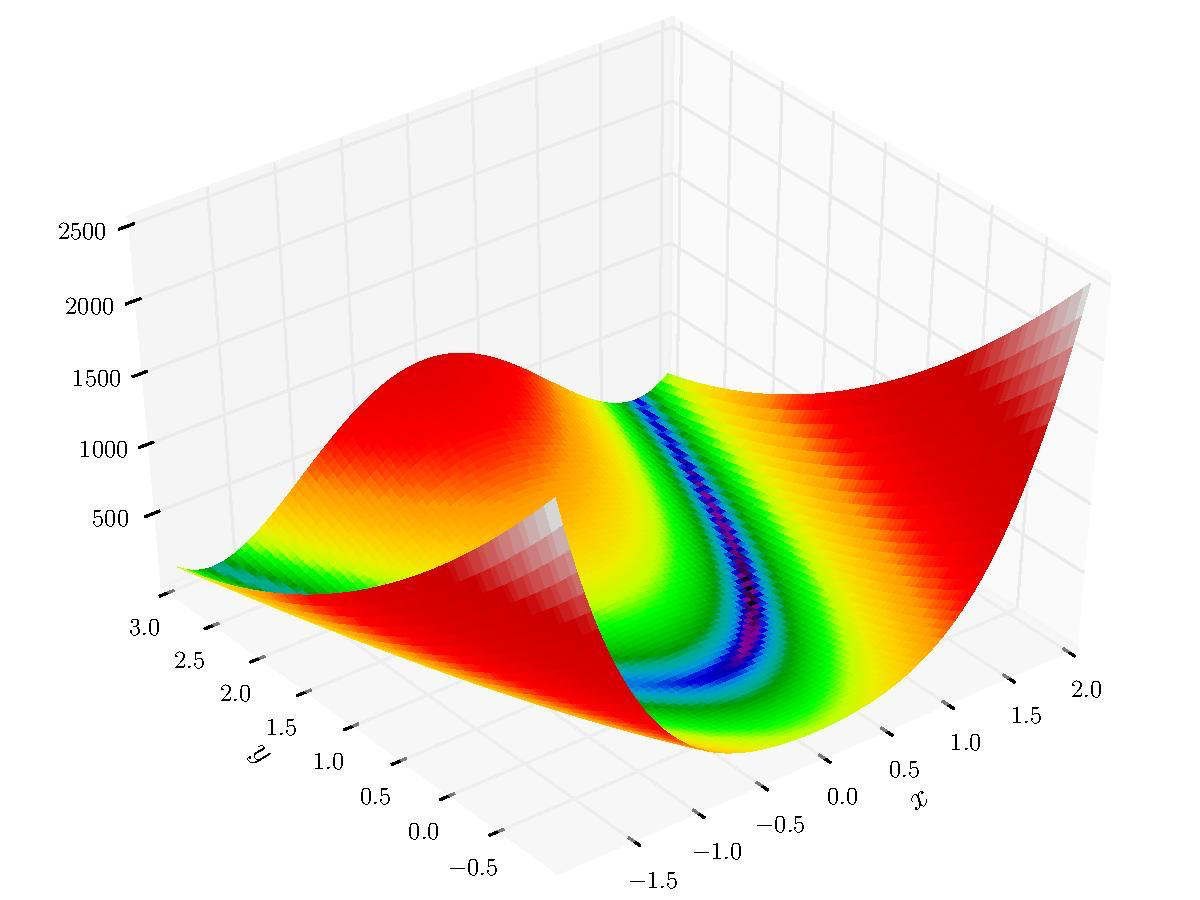

Here, we are going to use a brute force approach to finding the minimum/maximum (also known as "optimiziation") of a two dimensional function on a grid of points. Let us take a look at the function (also known as the objective function) that we are trying to optimize:

f = (1 - x)**2 + (y - x**2)**2

This is the two dimensional Rosenbrock function, which is used to test the robustness of an optimization method. It's not especially important that you understand the optimization component, in case you're curious, but it will be important to know that the script can work with or without arguments, as described below.

By default, our Python script will randomly select the boundary values of the grid that the optimization procedure will scan over. These values can be overridden by user supplied values.

To run the calculation with random boundary values, the script is executed without any arguments:

$ module load python/3.4

$ module load all-pkgs

$ python rosen_brock_brute_opt.py

To run the calculation with the user-supplied boundary values, the script is executed with four input arguments

python rosen_brock_brute_opt.py x_low x_high y_low y_high

where x_low and x_high are low and high values along the x-direction, and y_low and y_high are the low and high values along the y-direction.

For example, to set the boundary in the x-direction as (-3, 3) and the boundary in the y-direction as (-2, 2), run

$ python rosen_brock_brute_opt.py -3 3 -2 2

The directory Example1 runs the Python script with the default random values. The directories Example2, Example3 and Example4 deal with supplying the boundary values as input arguments.

Execution Script

Let us take a look at the execution script, cat scalingup-python-wrapper.sh

#!/bin/bash

module load python/3.4

module load all-pkgs

python ./rosen_brock_brute_opt.py $1 $2 $3 $4

The wrapper loads the the relevant modules (so our job will need to require servers in OSG that support OSG software modules) and then executes the python script rosen_brock_brute_opt.py with the four optional arguments.

Submitting Set of Jobs with Single Submit File

Now let us take a look at job description file

$ cd Example1

$ cat ScalingUp-PythonCals.submit

If we want to submit several jobs, we need to track log, out and error files for each job. An easy way to do this is to add the $(Cluster) and $(Process) variables to the file names.

# We can indicate the location of our executable, since it

# exists one directory level up. We'll let these first tests

# run our python script without giving it any arguments.

executable = ../scalingup-python-wrapper.sh

# Similarly, we can indicate the location of any other files

# that will need to be transfered into the job working directory.

# If we don't specify which output files to transfer back,

# HTCondor will just transfer back any new *files* from the job's

# working directory:

transfer_input_files = ../rosen_brock_brute_opt.py

# Additionally, we can indicate that our out/err/log files should

# be created by HTCondor within a subdirectory (or other location)

# so that they don't clog up our submission directory:

output = Log/job.out.$(Cluster).$(Process)

error = Log/job.error.$(Cluster).$(Process)

log = Log/job.log.$(Cluster).$(Process)

# Since we don't know the resource needs of our jobs, yet, we'll start with the below:

request_cpus = 1

request_memory = 1 GB

request_disk = 1 GB

Requirements = OSGVO_OS_STRING == "RHEL 6" && TARGET.Arch == "X86_64" && HAS_MODULES == True

# We'll use that trick to hold and release (to re-run) any jobs that

# happen to fail, in case their execute server was just missing some

# dependencies of our python program:

on_exit_hold = (ExitBySignal == True) || (ExitCode != 0)

PeriodicRelease = ( (CurrentTime - EnteredCurrentStatus) > 120 ) && (NumJobStarts < 5)

queue 10

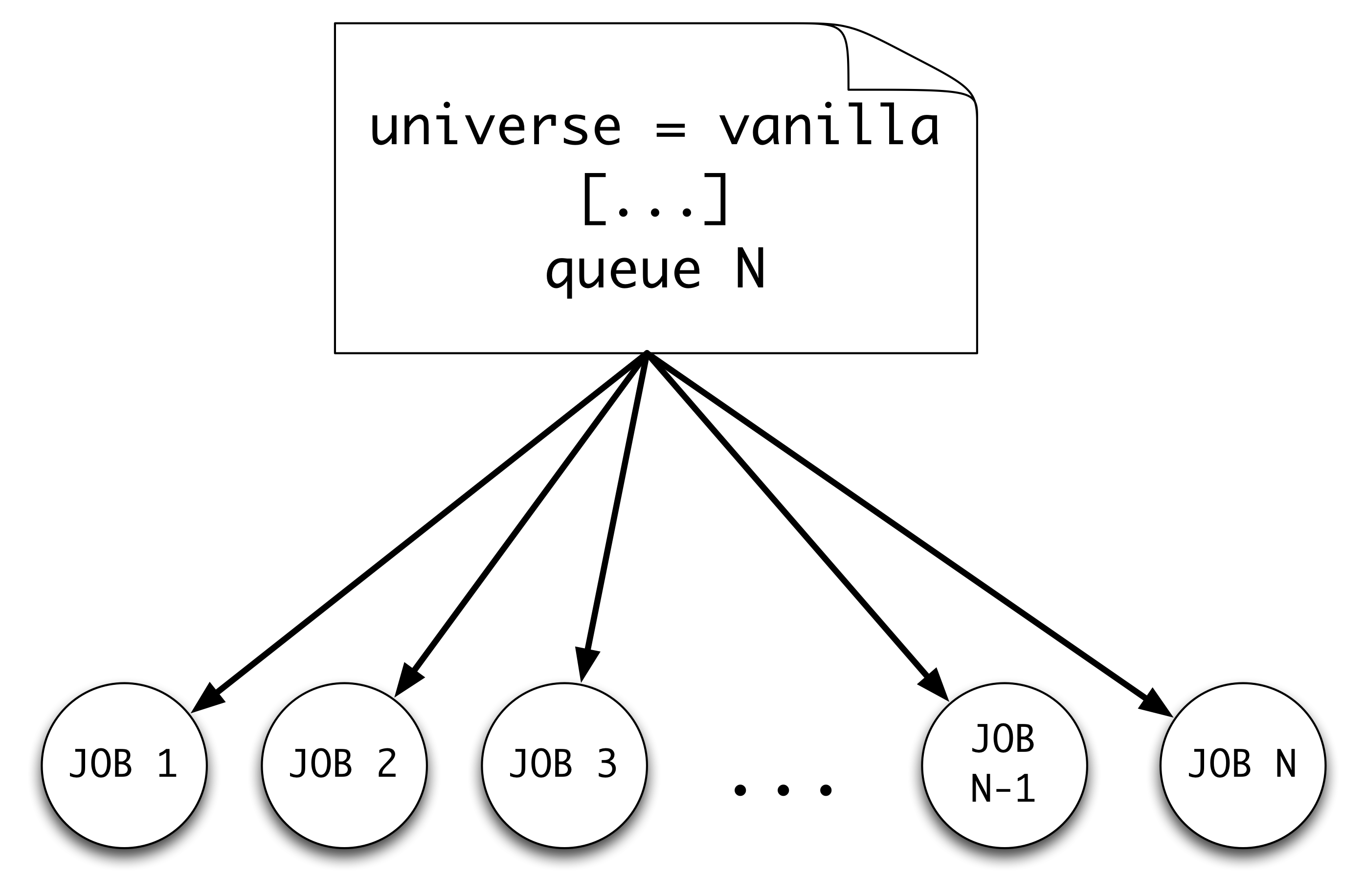

Note the queue 10. This tells HTCondor to queue 10 jobs (with unique process values) under one cluster number.

Let us submit the above job

$ condor_submit ScalingUp-PythonCals.submit

Apply your condor_q and watch (watch -n2 condor_q $USER) knowledge to see this job progress. After all jobs finished, execute the post_process.sh script to sort the results.

./post_process.sh

Other ways to use the queue command

Now we will explore another way to use the queue command, which is just one of several

described well in the (HTCondor Week User Tutorial)[https://agenda.hep.wisc.edu/event/1201/session/4/contribution/5/material/slides/1.pdf] (and in the HTCondor Manual)[http://research.cs.wisc.edu/htcondor/manual/current/2_5Submitting_Job.html#SECTION00352000000000000000].

In the previous example,

we did not pass any argument to the program and it used randomly-generated

boundary conditions. With the queue N approach, we could have passed the

$(Process) value as an argument, if 0-start integers made sense for our jobs or

if we were to have our program read the boundary values from different, numbered

input files for each job, but HTCondor give us a bit more flexibility. If we have some idea about where the minimum/maximum is, we can supply boundary conditions to the calculation through arguments. In our example, the minimum of the Rosenbrock function is located at (1,1).

Variable Creation with the queue command

In the previous example, we did not pass any arguments to the program,

so it used randomly-generated boundary conditions for each job.

If we have some idea about where the minimum/maximum is, we can

supply boundary conditions to the calculation as arguments by specifying

them in the arguments line of the submit file. The queue command has

additionaly options that allow us to submit a job for each of many sets of

parameters (passed as arguments into our main executable, which passes them

to our python script), ALL with just a single submit file.

Take a look at the job description file in Example4.

$ cd ../Example4

$ cat ScalingUp-PythonCals.submit

[...]

arguments = $(x_low) $(x_high) $(y_low) $(y_high)

[...]

queue x_low x_high y_low y_high from (

-9 9 -9 9

-8 8 -8 8

-7 7 -7 7

-6 6 -6 6

-5 5 -5 5

-4 4 -4 4

-3 3 -3 3

-2 2 -2 2

-1 1 -1 1

)

Now, submit the jobs:

$ condor_submit ScalingUp-PythonCals.submit

Apply your condor_q and watch knowledge to see this job progress. After all jobs finished, execute the post_process.sh script to sort the results.

./post_process.sh

Parameter Table in a Separate File

Because HTCondor queue statement is fairly flexible, we could have separated the parameter values on each line of the submit file with commas and/or spaces.

We could even define the same variables, but list them, instead, in a separate file, in which case our submit file would look like the below:

[...]

arguments = $(x_low) $(x_high) $(y_low) $(y_high)

queue x_low x_high y_low y_high from params.txt

And our separate file (params.txt) would need to include the same one-line-per-job set of parameters:

-9 9 -9 9

-8 8 -8 8

-7 7 -7 7

-6 6 -6 6

-5 5 -5 5

-4 4 -4 4

-3 3 -3 3

-2 2 -2 2

-1 1 -1 1

Make sure to check out the HTCondor User Tutorial and below Challenges for discussion of several more options for communicating the submission (and variations) of many jobs.

Challenges

-

If the list of parameters became large (more jobs and/or more parameters per job), we might want to instead create a different parameter file for each job, whose filename would need to be listed under

transfer_input_filesandarguments(with change to our python code, as well). Can you identify two ways to accomplish this goal, based upon the options described in the (HTCondor User Tutorial)[https://agenda.hep.wisc.edu/event/1201/session/4/contribution/5/material/slides/1.pdf]? -

What if you wanted to have the input parameter files for all jobs (from the above challenge) staged in a dedicated

parametersfolder within the submission directory (similar to how the log/err/out files are in a separateLogsfolder? (Hint: see the HTCondor User Tutorial, again.) -

What if you wanted each job's input parameter file and created output file of results to be in a different directory for each job? (Hint: see the

InitialDiroption in the HTCondor User Tutorial.)

Beyond the queue Keyword

For the largest workloads (more than ~10,000 jobs at a a time) or multi-step workflows with jobs that need to be submitted automatically in some sequence, there are workflow creation/management tools ((HTCondor's DAGMan)[] and (Pegasus)[]) that we recommend using.